Siim Tuksam

Among architects one often encounters the attitude that algorithmic architecture is a new phenomenon that professionals are forced to accept. Furthermore, it is seen as a danger to the architectural profession and digital culture is seen as something that devalues the profession.

In the architectural education edition of MAJA, the architect Jüri Soolep wrote: “The architect is turning into one of many consultants. For 30 years spatial planning has been gradually slipping into the hands of geographers, urban planners and landscape architects. The interior is taken over by interior architects, designers and fashion designers. The architect as the main author of the spatial solution is gradually dissolving.”¹ Soolep thinks in this context, architects should turn their attention to virtual realities as well. As one of the authors of “Interspace”², an interactive installation, bringing together the digital and physical public space, I obviously support such an approach. Architects must work with communal space in a new complicated context, inhabited by neoliberal individuals, both virtual and physical. Having intensively worked with this issue, I cannot dismiss the physical side of this super-networked continuum.

Identifying the symptoms

It is becoming increasingly evident that students of architecture are unable to relate to the traditional discourse. Or their projects lack fully developed ideas and the contemporary context. Many of the 2015 graduates of different schools of architecture in Estonia have acquired perfect technical skills when it comes to drawing and producing visuals. Even the quality of the models is increasing, although the materials and forms are rather dull. So at first glance one could agree that those projects really are worth a Master’s degree in architecture. However, on closer inspection, their lack of knowledge of the precedents and overall history of architecture becomes quite clear. There is certainly an enthusiasm for statistics, technical parameters, cost evaluations, development plans, polling interest groups, and yet the result of all of this is barely beyond a collection of diagrams, or in the worst case it severely hinders research. Twenty-five years ago architecture was taught through masterpieces. The works of Corbusier, Wright, Mies van der Rohe, Hoffman, Loos, Lutyens, Ledoux, Palladio, Bernini, Borromini and others were analysed in terms of their capacities, mass, construction, space, landscape design, vertical circulation or facade. Then, for some reason, universities began teaching architecture through the analysis of design data.³

Despite its benevolent, albeit probably misinformed, goal of trying to express the technological context of the 20th century, architecture has taken on a language that communicates through secondary components like paths, lifts, staircases, escalators, chimneys, pipes and disposal shafts. “Nothing could be further from the language of Classical architecture, where such features were invariably concealed behind the façade and where the main body of the building was free to express itself – a suppression of empirical fact that enabled architecture to symbolize the power of reason through the rationality of its own discourse..”4 While the architecture of the early 20th century mirrored the feats of the industrial revolution and was influenced by the austerity of cities heavily damaged in the wars, most of the large projects of today reflect the tyranny of Excel charts and architects’ inability to add anything meaningful in the contemporary algorithmic world.

A recent article by Rem Koolhaas starts with the question: “Will the digital revolution leave architecture behind?”5 Koolhaas thinks we are subjugated to a digital regime. Hand in hand with a new trinity in society – the French “liberty, equality, fraternity” has been now replaced with “comfort, security, sustainability” – the smart house and the smart city now flatten all of the previous practices of architecture and cast aside the smart artists, architects, commissioners, rulers and craftsmen who have understood the intelligent nature of cities and buildings for thousands of years.

Hypothesis

It is important to understand that banal architecture does not result from the digital tools architects use, but from a broader cultural, social and economic environment that comes with them. Maybe it is still possible that smart cities are developed together with an increased number of smart inhabitants, designers and architects. Instead of looking for new areas to work in, maybe it is possible for architects to come to terms with the algorithmic world and design it without forgetting about the traditions and collective intelligence that has developed over thousands of years.

Digital Architecture

Broadly speaking the influence of the digital on architecture is two-fold: firstly the cultural influence that focuses on developing design traditions and secondly the technicist influence that focuses on increasing utility and effectiveness. At one end of the scale there is digital architecture that developed out of certain branches of architecture in the 1980s. At the other end there is the all-encompassing grasp of BIM, which, on the one hand makes Hadid’s and Gehry’s designs possible; however, on the other hand it may also become a tool for imposing regulations and impeding creativity or enforcing the power of local government. Both contain prerequisites for creating great architecture, especially when the two are brought together.

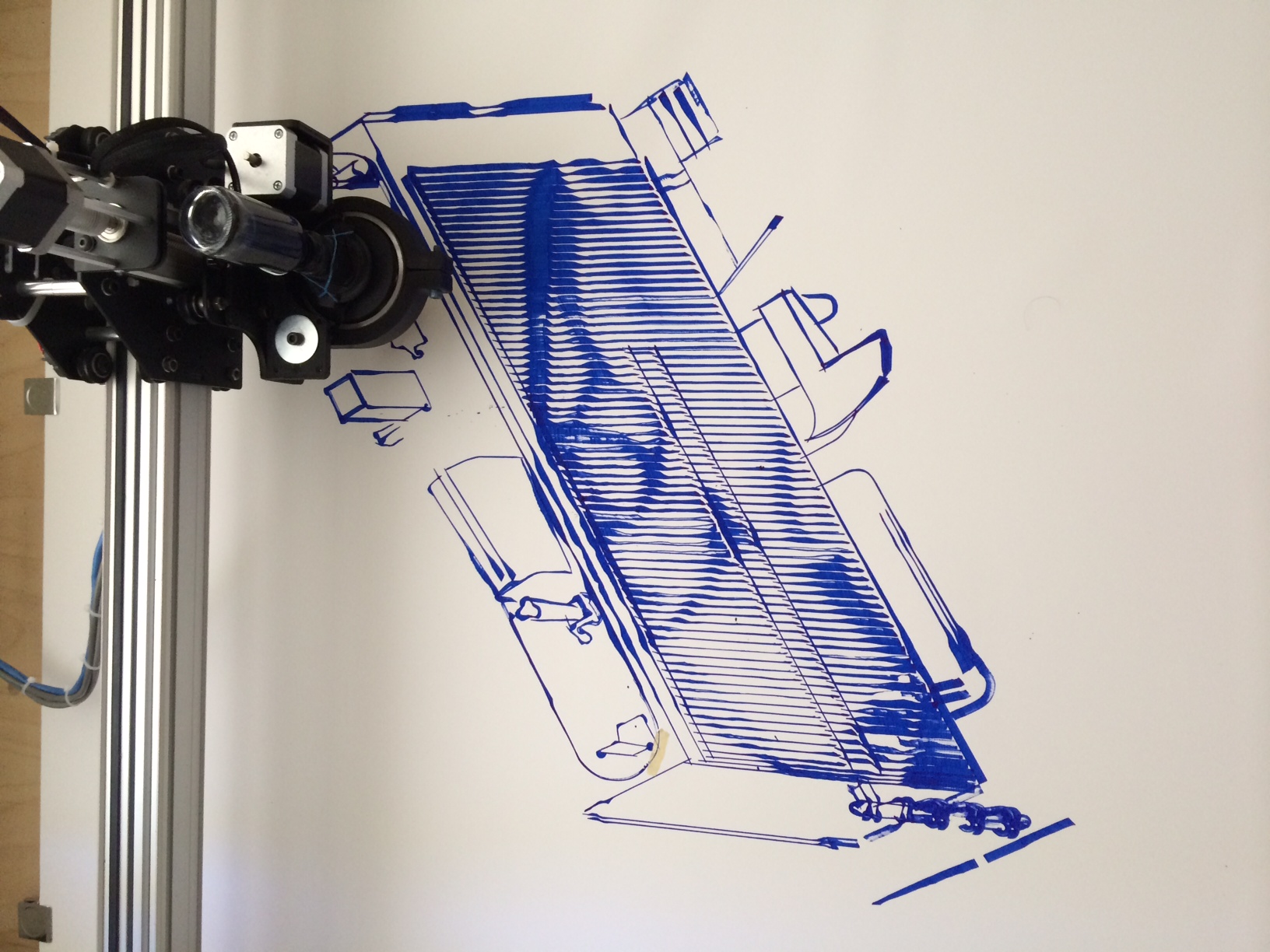

In the catalogue for “Archeology of the Digital” Greg Lynn describes the participants’ conscious relationship with the new tool: why they started using computers and how they followed their goals with extreme precision – they did not experiment aimlessly like many of the younger generation of digital architects do.6 When it comes to the early years of digital design, one could say the interactive, liquid, ‘blobist’, hyper-surfaced, virtual, print architecture of the 1990s was too speculative and oriented towards promises of the future. Yet seeing how fast the 3D printing technology, robotics, sensorics, analytics software, software for analysing construction information and other digital and networked technologies are, and how these technologies are used in the research facilities of universities, we can discuss what is possible today, here and now.